"Generic vasotec 10mg without prescription, prehypertension blood pressure".

By: N. Ayitos, M.A., Ph.D.

Co-Director, University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine

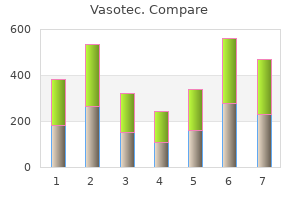

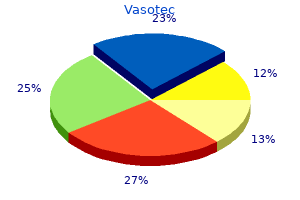

Outer thin membrane around an axon fiber Part V: Mission Control: All Systems Go 262 u Schwann cell: c blood pressure monitor walmart discount 10 mg vasotec. Negatively charged ion on the inner surface of the cell membrane B Polarization: a blood pressure diary buy cheap vasotec 5mg on line. Reshuffling of cell membrane ions; permeability of cell membrane D Cholinesterase: b hypertension 33 weeks pregnant buy cheap vasotec online. To remember, use the word “occipital” to bring to mind the word “optic,” which of course is related to visual activity. Controls motor coordination and refinement of muscular movement Chapter 15: Feeling Jumpy: The Nervous System 263 U Medulla oblongata: b. Contains the centers that control cardiac, respiratory, and vasomotor functions V Cerebrum: e. Contains the corpora quadrigemina and nuclei for the oculomotor and trochlear nerves X The largest quantity of cerebrospinal fluid originates from the c. Y The part of the brain that contains the thalamus, pituitary gland, and the optic chiasm is the a. Count them: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral — plus 1 tailbone (coccygeal). It has two divisions that are antagonistic to each other, meaning that one counteracts the effects of the other one. Lens : The area of the eyeball that contains cells that are sensitive to light is the b. They reshape the lens by contracting and relaxing as needed to bring things into focus. The structure in the eye that responds to the ciliary muscles during focusing is the b. Otherwise known as the eardrum, this membrane sometimes bursts or tears as a result of infection or trauma. Hairs in this structure are what ultimately send the signal down the auditory nerve. These little endolymph- filled sacs have hairs and chunks of calcium carbonate that detect changes in gravitational forces. Pinna Chapter 16 Raging Hormones: The Endocrine System In This Chapter Absorbing what endocrine glands do Checking out the ringmasters: Pituitary and hypothalamus glands Surveying the supporting glands Understanding how the body balances under stress he human body has two separate command and control systems that work in harmony Tmost of the time but also work in very different ways. Designed for instant response, the nervous system cracks its cellular whip using electrical signals that make entire systems hop to their tasks with no delay (refer to Chapter 15). By contrast, the endocrine system’s glands use chemical signals called hormones that behave like the steering mechanism on a large, fully loaded ocean tanker; small changes can have big impacts, but it takes quite a bit of time for any evidence of the change to make itself known. At times, parts of the nervous system stimulate or inhibit the secretion of hormones, and some hormones are capable of stimulating or inhibiting the flow of nerve impulses. The word “hormone” originates from the Greek word hormao, which literally translates as “I excite. Each chemical signal stimulates some specific part of the body, known as target tissues or target cells. The body needs a constant supply of hormonal signals to grow, maintain homeostasis, reproduce, and conduct myriad processes.

Attempts to determine the chronological age of a decedent at the time of death by any combination of methods involving the hard tissues will result blood pressure chart evening vasotec 10mg low cost, at best blood pressure medication side effects fatigue discount 5 mg vasotec with visa, in an estimated range pulse pressure 25 cheap vasotec amex. Under ideal circumstances, sufcient materials would be present to allow both osteological and dental approaches to age determination. Dental techniques, reported elsewhere in this volume, should correlate well with skeletal assessments of age in individuals up to around ffeen or sixteen years of age, and should provide reasonably comparable ranges up to about twenty. Because full maturation of the skeleton requires half again as long as the dentition, the former becomes increasingly more reliable as a basis for 144 Forensic dentistry estimating age. Te dentition is the only part of the skeleton that articulates directly with the outside environment. Terefore, the variable efects of diet, disease, traumatic insult, and accessory use are more apt to reduce the value of teeth in determining age in individuals beyond the mid-third decade, and in groups with chronically poor oral hygiene (who tend to appear older than their actual chronological age). Te sex and population membership of a dece- dent must be determined before applying any aging technique because these parameters signifcantly infuence rates of development, necessitating recali- bration of the result. Te details of osteological aging techniques are beyond the scope of this chapter and should be lef to experienced practitioners. A general approach to determination of age follows: Fetal period: Estimation of fetal developmental age assumes forensic importance in most jurisdictions because it is usually an indicator of viability. In instances of criminal death of a pregnant individual courts may decide whether to prosecute more than one homicide depending upon the age (i. Knowing the age of a discovered fetus may also assist in matters of identifca- tion. Usually, diaphyseal lengths may be used in various algorithms to estimate crown–rump length, which may then be translated into lunar age. Te timing of appearance of primary and some secondary ossifcation centers is also of use. Several sources give good accounts of the statistical reliability of various bones and measurements for both gross and radiographic fetal age determination. As noted, dental and osteological age should correlate well within this develop- mental interval. In recent years anthropologists and odontologists have become increasingly aware of diferences in rates of skeletal and dental maturation among various populations,34 and have begun to apply adjustments to their age estimates accordingly. Sixteen to thirty years: As attachment of primary and secondary ossif- cation centers occurs throughout the skeleton, attention turns to the completion of fusion of these centers. Numerous investigators have Forensic anthropology 145 established rating scales that describe the degree to which growth cartilages (metaphyses) have been replaced by bone, signaling the completion of that skeletal element or an articulation. Tese techniques usually take the form of a semantic diferen- tial, which describes changes in the appearance characteristics of a particular structure at known points in time based upon controls. Tirty years and beyond: As the last epiphyses (usually the medial clavicles) complete development, skeletal age may still be estimated, albeit with increasing error. As a result of endocrine-driven cellular interactions that constantly remove bone and replace it, the skeleton continues to “turn over” approximately every seven to ten years, remodeling itself to accommodate gravity and the mechani- cal habits of its owner. Alongside this process, the skeletal cartilages that separate and cushion bones undergo increased hardening with resulting grossly observable wear at the articulations, i. Age-related changes in the weight-bearing joints (ankle, knee, hip, sacroiliac, spine, etc. For example, as the marrow of long bones assumes a larger part of the hemopoetic burden with age, one can observe an advance of the apex of the marrow cavities in femora and humeri. As old cortical bone is scavenged by osteoclasts to maintain mineral homeostasis, new vascular pathways import osteoblasts that replace it. As the skeleton moves through time, the amount of unremodeled lamellar bone seen 146 Forensic dentistry in microscopic cross sections of cortex will diminish, and the num- ber of partly replaced structural units of old bone, osteon fragments, will increase. Tese changes have been documented and calibrated by various authors for a number of sites in the skeleton,43–45 and are of use in the aging skeleton because the process of turnover on which it is based extends throughout life.

Generic vasotec 5mg otc. blood pressure (idea tv).

Once in the lymphatic system blood pressure 3rd trimester order vasotec paypal, interstitial fluid becomes known as _______________ blood pressure chart in spanish proven 10mg vasotec. The lymph nodes of the lower extremities drain the _______________ blood pressure chart young adults order 10mg vasotec mastercard, _______________, and _______________. In the center of the nodules of the lymph node are areas called ______________________________. By keeping the interstitial fluid volume between tissue cells in balance, the lymphatic system also keeps the body in homeostasis. The thymus and spleen have no inbound (afferent) vessels, and Peyer’s patches and tonsils don’t have much to do with lymph circulation. It provides both a tissue framework and a type of netting to hold clusters of lymphocytes. This reaction occurs as the battle begins in your immune system at the cellular level. Chapter 11: Keeping Up Your Defenses: The Lymphatic System 193 q The lymphatic organ that stops growth during adolescence and atrophies with aging is the a. Here’s a memory tool that only word-play students will love: “The thymus runs out of thyme. When you remember where the pharynx is — the back of the throat — this question becomes more obvious. Break this question into parts and it becomes easier to locate which gland is being referenced: Superior means “upper,” media– means “middle” (or “midline”), and –stinum refers to the ster- num, or breastbone. It recycles critical components from the spent blood cells and sends them to the bone marrow to be turned into fresh cells. A The lymph system offers an alternative route for the return of the tissue fluid to the blood- stream. True B The fluid surrounding the cells that will enter the lymph capillaries is called interstitial fluid. True C Lymph from the lymph vessels flows into the right thoracic duct and the left thoracic duct. False F The thymus gland is functional in the early years of life and is most active in old age. G Tonsils function to protect against pathogens and foreign substances that are inhaled or ingested. True H The spleen functions in the removal of aged and defective blood cells and platelets from the blood. This statement doesn’t make much sense because “gastric” refers to the digestive system. J The thoracic duct originates from a triangular sac called the chyle cistern (or cisterna chyli). M Peyer’s patches are masses of lymphatic nodules found in the distal portion of the small intes- tines. You may be tempted to write “thoracic duct” here, but that’s incorrect because the duct is the largest vessel, not the largest organ. P In the center of the nodules of the lymph node are areas called germinal centers. When you read “germinal,” think of the word “germinate,” and then think of a place where lymphocytes can sprout and mature. Chapter 12 Filtering Out the Junk: The Urinary System In This Chapter Putting the kidneys on clean-up duty Tracking urinary waste out of the body f you read Chapter 9 on the digestive system, you may be chewing on the idea that undi- Igested food is the body’s primary waste product. We make more of it than we do feces — in fact, our bodies are making small amounts of urine all the time — and we release it more often throughout the day. Most important, urine captures all the leftovers from our cells’ metabolic activities and jettisons them before they can build up and become toxic.

The boundary model proposes a form of dual regulation blood pressure chart in spanish cheap 10mg vasotec amex, with food intake limited either by the diet boundary or the satiety boundary blood pressure chart uk nhs order cheap vasotec on line. The boundary model has also been used to examine differences between dieters blood pressure medication increased urination discount 5 mg vasotec with visa, binge eaters, anorexics and normal eaters. Primarily this has been described in terms of a breakdown in the dieter’s self control reflecting a ‘motivational collapse’ and a state of giving in to the overpowering drives to eat (Polivy and Herman 1983). Ogden and Wardle (1991) analysed the cognitive set of the disinhibited dieter and suggested that such a collapse in self control reflected a passive model of overeating and that the ‘what the hell effect’ as described by Herman and Polivy (1984) contained elements of passivity in terms of factors such as ‘giving in’, ‘resignation’ and ‘passivity’. In particular, interviews with restrained and unrestrained eaters revealed that many restrained eaters reported passive cognitions after a high calorie preload including thoughts such as ‘I’m going to give into any urges I’ve got’ and ‘I can’t be bothered, it’s too much effort to stop eating’ (Ogden and Wardle 1991). In line with this model of overeating, Glynn and Ruderman (1986) developed the eating self-efficacy Fig. This also emphasized moti- vational collapse and suggested that overeating was a consequence of the failure of this self-control. An alternative model of overeating contended that overeating reflected an active decision to overeat and Ogden and Wardle (1991) argued that implicit within the ‘What the hell effect’ was an active reaction against the diet. This hypothesis was tested using a preload/taste test paradigm and cognitions were assessed using rating scales, interviews and the Stroop task which is a cognitive test of selective attention. The results from two studies indicated that dieters responded to high calorie foods with an increase in an active state of mind characterized by cognitions such as ‘rebellious’, ‘challenging’ and ‘defiant’ and thoughts such as ‘I don’t care now in a rebellious way, I’m just going to stuff my face’ (Ogden and Wardle 1991; Ogden and Greville 1993 see Focus on research 6. It was argued that rather than simply passively giving in to an overwhelming desire to eat as suggested by other models, the overeater may actively decide to overeat as a form of rebellion against self-imposed food restrictions. This rebellious state of mind has also been described by obese binge eaters who report bingeing as ‘a way to unleash resentment’ (Loro and Orleans 1981). Eating as an active decision may at times also indicate a rebellion against the deprivation of other substances such as cigarettes (Ogden 1994) and against the deprivation of emotional support (Bruch 1974). This has been called the ‘masking hypothesis’ and has been tested by empirical studies. For example, Polivy and Herman (1999) told female subjects that they had either passed or failed a cognitive task and then gave them food either ad libitum or in small controlled amounts. The results in part supported the masking hypothesis as the dieters who ate ad libitum attributed more of their distress to their eating behaviour than to the task failure. The authors argued that dieters may overeat as a way of shifting responsibility for their negative mood from uncontrollable aspects of their lives to their eating behaviour. This mood modification theory of overeating has been further supported by research indicating that dieters eat more than non-dieters when anxious regardless of the palatability of the food (Polivy et al. Overeating is therefore functional for dieters as it masks dysphoria and this function is not influenced by the sensory aspects of eating. This has been called the ‘theory of ironic processes of mental control’ (Wegner 1994). For example, in an early study participants were asked to try not to think of a white bear but to ring a bell if they did (Wegner et al. The results showed that those who were trying not to think about the bear thought about the bear more frequently than those who were told to think about it. A decision not to eat specific foods or to eat less is central to the dieter’s cognitive set. This results in a similar state of denial and attempted thought suppression and dieters have been shown to see food in terms of ‘forbiddenness’ (e. Therefore, as soon as food is denied it simultaneously becomes forbidden and which translates into eating which undermines any attempts at weight loss. Restrained and unrestrained eaters were given a preload that they were told was either high or low in calories and then were either distracted or not distracted. The results showed that the restrained eaters ate particularly more than the unrestrained eaters in the high calorie condition if they were distracted.